Federal courthouse in Big Stone Gap celebrating 100 years

Bristol Herald Courier,

November 10, 2011

A man sang and played a banjo in the courtroom Wednesday, but none of the seven judges in attendance ruled him out of order.

Bristol Herald Courier

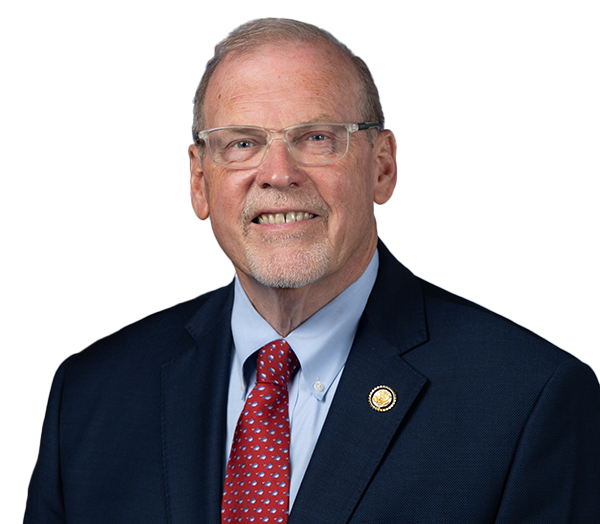

By Debra McCown © November 10, 2011 Full story here BIG STONE GAP, Va. -- A man sang and played a banjo in the courtroom Wednesday, but none of the seven judges in attendance ruled him out of order. Like him, they were celebrating the 100 years of history held by Big Stone Gap’s federal building, which houses a post office on the first floor and, at the top of a narrow staircase, an ornately designed courtroom. “It may be the first time we’ve had a banjo in court,” joked local musician Ron Short, before he entertained the crowd with two songs about Big Stone Gap and its history. “I’m absolutely certain there have been banjo players, and some of them from Pound, because that’s where my family’s from.” Order on the frontier In a cultural region where families are often proud of outlaw roots, Short wasn’t the only one attesting to the lawlessness that once existed in this mountainous corner of Virginia. U.S. Magistrate Judge Pamela Meade Sargent, a Wise County native, said some of her relatives too had run afoul of the law – for making moonshine. She knows they were convicted, she said, but she hasn’t found a record of them being convicted in Big Stone Gap. “This courthouse is just a symbol,” she said, a century after its cornerstone was laid in 1911 and the building constructed of granite, marble and oak. “We’re honoring that symbol today of what that courthouse is: It’s just a justice system which today, 100 years later, is still the greatest justice system in the world,” she said. “This courthouse is just a symbol of the place where they [people] could come, where their individual property rights could be enforced and protected.” As the story goes, bootleggers and bandits weren’t all that uncommon back in the early days of bustling Big Stone Gap. The courthouse, built in the midst of what has been described as a Wild West-like atmosphere in the boom times of the early 20th century, was involved in bringing order in this place near the convergence of three states, said Sharon Ewing, park manager of the Southwest Virginia State Historical Park “Big Stone Gap had all these things going on, a lot of people coming in, they had a lot of cultural activities going on,” Ewing said, “but they also had some components of what we would consider the western frontier. … You had some lawlessness.” Courthouse history Back in the 1870s, the town of Big Stone Gap was called Three Forks, Ewing said. The first post office there was inside a general store owned by one of three local families upon whose farmland the town was built. “As the area developed, there was iron ore discovered here, and later coal was discovered, so when you go back to when the town becomes Big Stone Gap, we’re talking about the 1890s,” she said. “There were numerous hotels here. It was a bustling town. You had investors coming in to make their fortunes in the coal mines. Big Stone Gap was being promoted in the papers in Philadelphia as the new Pittsburgh of the South.” In that time, Ewing said, the town featured numerous cultural activities and wooden sidewalks. But with that came ruffians, and local policing efforts to rein them in. Court was first held in the Minor Building, which also still stands on the town’s main street. With a flurry of construction going on downtown, the courthouse was planned in 1908 and four building lots purchased in 1909 for $6,000. Congress approved money for construction in 1910 and 1911, and the project was completed in 1912 – for $90,882. The building was named for C. Bascom Slemp, a long-serving U.S. Congressman of that era, and included in the project is what was then a forward-thinking improvement: electric lighting. The court there was closed in the 1950s, Ewing said, but Judge Glen Williams had it re-established in 1978. “He wanted to make it more convenient for the citizens of our area,” she said, explaining the hours of driving it can sometimes take to reach Abingdon – the site of Virginia’s next nearest federal courthouse – from places like rural Lee County. Nancy Bailey, mayor of Big Stone Gap, said it was the work of four women in the 1970s who got the building on the National Register of Historic Places – at a time when it was slated for demolition so a new post office could be built. The next 100 years? With speculation in recent months that the courthouse in Big Stone Gap might be closed, several of the speeches made Wednesday dealt with the need to keep it open. In an interview after the centennial ceremony, U.S. District Judge James P. Jones said he’s not been given any information indicating that the courthouse is to be closed. But it is, he said, a budgetary issue. “Because of the budget problems with our government today, the folks in Washington look at ways to economize, and one way is to look at courthouses, so it may be that this courthouse along with others may be looked at,” Jones said, “but we are very hopeful that there are a lot of arguments for this courthouse to remain open.” Jones is the judge who hears most of the cases in Big Stone Gap. “As long as I’m on the bench, I want to continue to do that,” said Jones, who indicated he has no plans to retire. In a brief address, U.S. Rep. Morgan Griffith echoed support for the Big Stone Gap courthouse. “I agree with Ms. Ewing that if you travel the roads of this part of Southwest Virginia, sometimes it takes a little longer than it might look like it’s going to take on a map,” he said, “and it’s very important to the citizens of this area to continue to keep this courthouse open.” Unique value Henry Keuling-Stout, speaking for attorneys who practice in the area, said the courthouse is uniquely situated to serve people with deep roots in Southwest Virginia, Northeast Tennessee and Eastern Kentucky. “Being a federal court we’re dealing with other states to a large extent, and people from other states, and we stand here in the middle of three states,” he said. “This dynamic of being close to other states makes necessary the presence and continuation of this particular Big Stone Gap court.” Secondly, he said, “Lawyers near and far find something special about this court and this place.” That is found not just in the 30-foot ceilings and massive windows, he said, but in the uncommon directness to the communication among judge, jury and witnesses, with the witness chair set squarely in front of the jury and judge. Third, Keuling-Stout said, “This court is a place for the voice of our people.” “We are a less-than-fully-understood people in far Southwest Virginia, with strong convictions,” he said. “We as people here need this place to speak. The country needs this court as a place to hear us speak, and we lawyers ask that this place continue for at least another 100 years to function as an important space for our people to plead, define and defend their, our, federal American rights.” |

Stay Connected

Use the form below to sign up for my newsletter and get the latest news and updates directly to your inbox.